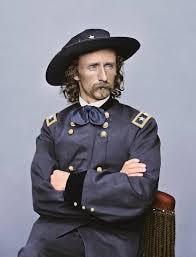

THEE, General Custer’s Personal Rifle

Are you kidding me, I just ruined a master piece of history, I know nothing. The Battle of Big Horn Relic!....Issue#13

ifOnlyi…were smarter back then, and took the time to listen and respect my elders’ recommendations and not touch the Rifle. Perhaps sent it off to an expert to save what wood was left. This was something of importance, Bighorn Importance! Now it was ruined, and I had to live with that.

As a new student, I immediately signed up for the Woodshop class. I just thought it would make my days go easier. I have to admit, though, that I ended up loving woodshop and taking the course for all four years.

In my first year of woodshop, I wanted to repair a gift that was given to me by Boris the Baron. You may remember him from my Substack Issues #6 & 7. As a goodbye gift when I left Portugal, Boris gave me one of General Custer’s Personal Rifles. It had Custer’s logo etched in the metal, and there were flaws, to say the least.

Boris said that it was very special. What did I know, special at 13 years of age and a rifle looking like this? Termites had eaten the wood over the past 98 years.

Boris told me it was used in what was called ‘General Custer’s last stand’. I learned later that that was indeed the Battle at Little Bighorn.

Battle of the Little Bighorn: Custer’s Last Stand

Article Title: Battle of the Little Bighorn

Author: History.com Editors

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, fought on June 25, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory, pitted federal troops led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer (1839-76) against a band of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. Tensions between the two groups had been rising since the discovery of gold on Native American lands. When a number of tribes missed a federal deadline to move to reservations, the U.S. Army, including Custer and his 7th Cavalry, was dispatched to confront them. Custer was unaware of the number of Indians fighting under the command of Sitting Bull (c.1831-90) at Little Bighorn, and his forces were outnumbered and quickly overwhelmed in what became known as Custer’s Last Stand.

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse (c.1840-77), leaders of the Sioux on the Great Plains, strongly resisted the mid-19th-century efforts of the U.S. government to confine their people to Indian reservations. In 1875, after gold was discovered in South Dakota’s Black Hills, the U.S. Army ignored previous treaty agreements and invaded the region. This betrayal led many Sioux and Cheyenne tribesmen to leave their reservations and join Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse in Montana.

By the late spring of 1876, more than 10,000 Native Americans had gathered in a camp along the Little Bighorn River–which they called the Greasy Grass–in defiance of a U.S. War Department order to return to their reservations or risk being attacked.In mid-June, three columns of U.S. soldiers lined up against the camp and prepared to march. A force of 1,200 Native Americans turned back the first column on June 17.

Five days later, General Alfred Terry ordered George Custer’s 7th Cavalry to scout ahead for enemy troops. On the morning of June 25, Custer, a West Point graduate, drew near the camp and decided to press on ahead rather than wait for reinforcements.At mid-day on June 25, Custer’s 600 men entered the Little Bighorn Valley. Among the Native Americans, word quickly spread of the impending attack.

The older Sitting Bull rallied the warriors and saw to the safety of the women and children, while Crazy Horse set off with a large force to meet the attackers head on. Despite Custer’s desperate attempts to regroup his men, they were quickly overwhelmed. Custer and some 200 men in his battalion were attacked by as many as 3,000 Native Americans; within an hour, Custer and all of his soldiers were dead.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also called Custer’s Last Stand, marked the most decisive Native American victory and the worst U.S. Army defeat in the long Plains Indian War. The demise of Custer and his men outraged many white Americans and confirmed their image of the Indians as wild and bloodthirsty. Meanwhile, the U.S. government increased its efforts to subdue the tribes. Within five years, almost all of the Sioux and Cheyenne would be confined to reservations.My goal was to repair this rare piece of history. The easy part was taking it apart, now what? For nearly 4 years, as just one of my projects, I tried to repair using loads and loads of wood putty, sanding, and whatever else I was told could be used. Little did I know I was making a mess of this precious rifle. It’s like someone asking if you can fix my engine, and you say yes. But you never even drove a car. That’s me!

My teacher didn’t have the passion for fixing something he knew should not have been touched or fixed. The rifle was full of woodworm holes, and now it was destroyed, a huge piece of history gone forever. How sad!

Nothing could be done to make it rise again. The metal was polished up and shiny, for sure, as I was an expert at polishing, right? (Reading earlier stories will help you understand the comment about polishing!). This was a disaster! I should have listened. Sadly, listening and taking heed just wasn’t my style as a teenager.

ifOnlyi…. short stories are published chronologically, and follow my life growing up in California from 4 years old. If you’ve just found me, the stories will come together when you start reading from….Issue #1

great 🙃🙃🙃🤗🤗🤗😘😘😘😍😍😍🥰🥰🥰